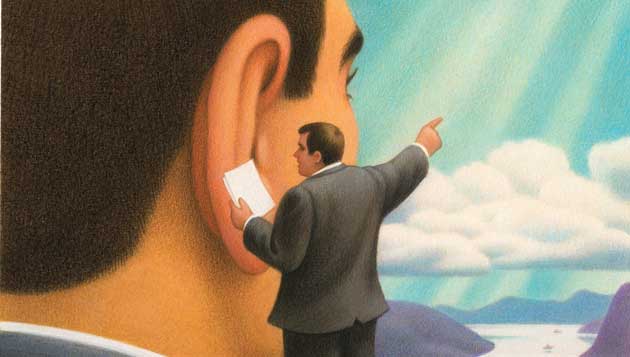

Managing through the eyes and ears of staff

Employees who find their work frustrating, boring and worthless have found their hero in Scott Adams’ world famous cartoon character Dilbert, the nine-to-five man who lets us know just how bad managers can be at their jobs. But Julian Birkinshaw, Vyla Rollins and Stefano Turconi believe that bad bosses can change to become true leaders.

Most books written on management and leadership are written from the perspective of the manager. These books are typically based on interviews with managers. The authors of such books often offer advice aimed at helping managers do their jobs better.

While there is value in such books, they pay far too little attention to the fears, doubts, aspirations or needs of the employee. This focus on the person doing the managing, rather than the one being managed, perpetuates many traditional assumptions about management being a top-down and control-oriented activity.

In our recent research (which involved interviews with more than 50 employees across a dozen companies as well as questionnaire data from more than 200 employees), we took an employee-centred approach to management - starting with the view that management should be about percieving the world through the eyes and ears of the employee. According to this perspective, the job of the manager is essentially to enable employees to do their best work, to help them reach their own personal goals while also delivering on the organisation’s goals.

This employee-centred approach seeks to recast the role of the manager as one of tapping into an employee’s strengths, enabling her aspirations and negating her fears.

Each employee has a unique set of skills and motivations, the right balance for one person is likely to be the wrong balance for the next.

Thus, we sought employees’ views on the aspects of their work that they found motivating and engaging, as well as the various concerns, fears or frustrations that got in the way of them delivering their best work. We then asked them more narrowly about their relationship with their immediate boss and the things he or she did to shape the working environment for individual employees in a positive or negative way.

What employees want

There were five characteristics that employees seemed to recognise as most important and valuable:

- Having responsibility for doing something worthwhile

- Being given a high level of freedom for how results are achieved

- Having an opportunity to extend oneself and to develop expertise

- Being given an opportunity to work with good colleagues

- Achieving recognition for doing a good job.

What is surprising is that so many people, in very different working environments, find themselves doing work that does not have these attributes. Moreover, it is worth underlining that money is nowhere to be seen. Only some salespeople, who have a large variable component to their pay, mentioned it. Likewise, there was no discussion of the physical working environment.

The five characteristics were consistently mentioned across a wide variety of contexts - from white-collar office workers to factory machinists, frontline hotel employees and IT help desk workers. Most working environments, we believe, would benefit by utilising these broad principles in their management practices.

What frustrates workers

Effective management is potentially as much about getting rid of the negatives as it is about enhancing the positives.

The list of fears, concerns and frustrations mentioned by employees was very long but the major sources of fear or concern, in hierarchical order, boiled down to seven issues:

- Lack of opportunities for personal development

- Fear of failing to deliver on (high) expectations

- Concern with the stress of the work

- Frustration with ineffective processes

- Concern about not fitting in

- Concern with uncertainty and change

- Fear of redundancy

It is always good to know what your employees are worrying about, what their most immediate and easily articulated concerns are. The things that are worrying your employees may also be indicative of their overall situation, including the things that they are content with. For example, if your employees express concerns about their personal development and their worries about not delivering against expectations, it is likely that they are not worried about job security and fitting in, the lower rungs of the hierarchy of fears. Equally, for those employees who express concern about job security and fitting in, it is unlikely the higher rungs on the hierarchy are even on their list of concerns. In which case, any initiatives directed at higher-level concerns that do not first address lower-level concerns are likely to be a waste of time.

Finally, the hierarchy of fears applies only to the workplace, and work is only one part of an individual’s life. The workplace cannot satisfy all an employee’s needs, but we believe it has the potential to satisfy many of them.

Good boss? Bad boss?

We asked respondents what made their bosses effective or ineffective. We also asked them about their best and worst bosses ever.

A good boss gives employees challenging work to do, creates space for them to do it, provides support when needed, gives recognition and praise and is not afraid to make tough decisions. A bad boss tends to provide confusing or unclear objectives, micromanages and meddles, is selfish and focused on his own agenda, provides little and mostly negative feedback and dithers.

Our research led us to two difficult questions: first, if it is so easy to draw up a list of what makes an effective manager, why are there so many bad managers out there? Further, given that this gap exists and has existed for a long time, what can we do about it?

Managerial hurdles

We asked many of our interviewees why potentially good managers become bad ones. The answers are grouped into three basic categories.

Managing well is harder than it seems. For most aspects of management, it is possible to get it wrong in both directions. So, while giving employees space to act is a good thing, it is also possible to give them too much space. Providing challenging tasks is good, but impossible tasks are not. Balance is the key in both areas. But what makes this really difficult is that each employee has a unique set of skills and motivations, the right balance for one person is likely to be the wrong balance for the next.

There just are not enough hours in the day. Managers have competing priorities and limited time. Many managers have five or six people reporting to them (and, today, some managers have many more), each with different needs. Throw all these things into the mix and then add whatever economic or corporate crisis has just hit, and it is no surprise that even the most well-intentioned and skilled executives fail to do the managerial part of their jobs well on a

consistent basis.

Managing well requires non-intuitive behaviour. The third reason why many managers fail to walk the talk is that being a good manager requires them to act in non-intuitive or ‘unnatural’ ways. There is a great deal of academic research looking at the natural predispositions we have as humans. This research shows, for example, that we are fairly selfish, control-oriented and risk-averse. There is nothing wrong with these traits per se, but these are not the traits of a good manager.

Like this story? Share it.